THE TUSKEGEE AIRMEN STORY: TECHNICAL TRAINING IN MILITARY AVIATION FOR BLACKS

Chanute Army Air Field, Illinois, was chosen as the facility for the technical training of the ground crew and the Tuskegee, Alabama area was selected to conduct the training for the pilots.

Chanute Field, Illinois

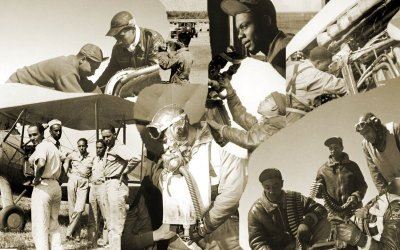

The Army Air Corps had initiated a program for training Aviation Cadets (non flying) in three specialties just a few months earlier. The Aircraft Maintenance School was at Chanute Field, the Armament School at Lowry Field, Colorado, and the Communications School at Scott Field, Illinois. Since the cadets and enlisted men were all segregated at Chanute, Lowry and Scott Fields sent instructors on detached duty and provided equipment to conduct Engineering, Armament and Communications courses at Chanute.

At Chanute, the enlisted personnel were quartered together in World War I barracks across the field from the main base. A portion of the barracks was divided off to provide separate space for the cadets to eat, sleep, and to study. Since Chanute was the primary Air Corps Mechanics School, the Negro engineering cadets attended classes with the white cadets. Cadets in communications and armament took their classes with the colored enlisted men.

Upon completion of six months classroom training, the cadets would serve ninety days "on the line" at an operational AAF base for practical experience and then be commissioned second lieutenants. This course of training was to develop personnel qualified to serve as squadron officers in their fields of expertise. These particular officers, of course, were to be made available to the only Black Army Air Forces squadron that had been authorized at that time.

On June 4, 1941, six aviation cadet enlistees reported to Chanute Field, Rantoul, Illinois, for specialized training in Maintenance Engineering, Armament, and Communications. Upon arrival they were immediately assigned to the 99th Pursuit Squadron, which had been activated at Chanute on March 21, 1941. By that time about two hundred and seventy-eight carefully selected enlisted men were already there in training.

Tuskegee Army Flying School

An area in Alabama near Tuskegee Institute was selected as the site to build the facilities to train Black military pilots. This location was in the heart of a region of the country where, at that time, the strongest and most vociferous forces of resistance to their true citizenship had been nurtured since the end of slavery.

An area in Alabama near Tuskegee Institute was selected as the site to build the facilities to train Black military pilots. This location was in the heart of a region of the country where, at that time, the strongest and most vociferous forces of resistance to their true citizenship had been nurtured since the end of slavery.

Consequently, some of the individuals and organizations which had worked from the outset of the struggle to overcome the racial barrier to military aviation training, believed that segregation itself was a form of discrimination, and voiced strong objections to the selection of the Tuskegee, Alabama area as the site for the Air Corps' pilot training program.

The NAACP disliked the idea of segregated training. Also the National Airmen's Association, a Black organization, took a stronger position at one of its meetings, by passing a resolution condemning the establishment of the segregated squadron. Judge Hastie was unhappy with the Institute for accepting and monopolizing Black pilot training, and with the Air Corps for locating the flying training facilities in Alabama. He believed that Tuskegee and the Air Corps were involved in an unholy alliance to keep Blacks segregated.

So, those opposed to the idea of locating this military flight training program at Tuskegee were caught up in a dilemma. Although they were strongly against any kind of segregation, they knew Tuskegee was an opportunity for Blacks to fly in the Air Corps.

In the meantime, a contract was given to Tuskegee Institute for the primary training of all Negro flying cadets. Also, during this early part of 1941, a contract to build the Tuskegee Army Air Field was awarded to McKissack and McKissack, an organization headed by a Black architect and contractor. The work of constructing the airfield began on June 23, 1941.

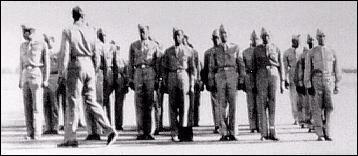

The first class, which was designated 42-C, began with 13 trainees (12 cadets and one military officer), and their training started on July 19, 1941.

In the 1940s, military pilot training consisted of four phases of instruction: (I) Preflight, (2) Primary, (3) Basic, and (4) Advanced. All phases included military instructions and protocol, and physical training. Preflight was all ground school with flying training first introduced in primary, and the associated technical subject matter progressed with each phase. In the first part of November 1941, the initial ground crew of the contingent of the 99th arrived at the partially completed Tuskegee Army Air Field. On November 8, the flying cadets completed their primary flying training at Tuskegee Institute's Moton Field, and were transferred to the new army airfield to begin training in higher performance aircraft and military tactics.

Almost immediately after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the non-flying cadets, who had completed their courses in ground-support disciplines at Chanute, were commissioned after only a month of training on the line at the Tuskegee Army Air Field. The armament officer, one of the communications officers and one of the maintenance officers were eventually assigned to the 99,h Fightet Squadron. The other communications officer went to base communications and the second maintenance officer was assigned to the AAF Service Detachment #99 as Commander and Engineering Officer.

The first pilot training class comprised: Captain Benjamin 0. Davis, Jr.; John C. Anderson, Jr.; Charles Brown; Theodore Brown; Marion Carter; Lemuel R. Custis; Charles DeBow; Fredrick H. Moore; Ulysses S. Pannell; George S. Roberts; William Slade; Mac Ross; and Rodrick Williams. Captain Davis trained in grade, since he had graduated from the U. S. Military Academy at West Point in 1936. The other 12 members of the class were required to have a four-year college degree, even though the minimum educational requirement at the time was two years of college training.

This higher level of training requirement for Negroes was relaxed, subsequently, to two years of college, then one year, and finally, only a high school diploma. However, regardless of the level of formal education, all cadet applicants had to pass minimum requirements on the Army General Classification Test (AGCT), and rigid physical/medical criteria.

Of the 13 students that began in this first class, five completed the training and received their wings on March 7, 1942. The five graduates were:

- Captain Benjamin 0. Davis, Jr.

- Second Lieutenant Lemuel R. Custis

- Second Lieutenant Charles DeBow

- Second Lieutenant George S. Roberts

- Second Lieutenant Mac Ross.

At the outset, the base was under the direction of a White commander and a White staff and all of the flying instructors at this field were White. After a couple of false starts, the Air Corps made an excellent selection of a base commander in the person of Lieutenant Colonel, later Brigadier General, Noel F. Parrish. Parrish applied his broad knowledge and understanding of racial problems and concerns during his command of the base. He devoted his heart and soul towards providing a fair opportunity in military aviation for trainees at Tuskegee Army Air Field.

Over a period of about a year, he was able to remove the first doubts about Black performance in the Air Corps. It was the development of a resounding yes that they could be taught to fly and fight using the same standards as the Air Corps was applying to Whites.

Over a period of about a year, he was able to remove the first doubts about Black performance in the Air Corps. It was the development of a resounding yes that they could be taught to fly and fight using the same standards as the Air Corps was applying to Whites.

Parrish's job was extremely difficult. He had to comply with War Department regulations requiring segregation of the races and he had to maintain some level of segregation to keep the White Air Corps base complement happy, as well as the hostile southern White population of the State of Alabama that surrounded the base.

In a sense, Tuskegee Army Air Field, while conducting the controversial flight training, became a model for keeping Blacks "in their place" that the most zealous segregationists could approve.

The training program at the Tuskegee Army Flying School was an evolving process throughout the entire existence of the school. The setup of the base and the way that it was required to operate under Army Regulations, which was the same as any segregated arrangement anywhere in the country, created a sense of discrimination and deprivation in the minds of many of the cadets in training there. This created a feeling of apprehension about the fairness of the system that caused an inordinate amount of psychological stress especially for those in flying training.

Along with the racial pressures, the cadets at Tuskegee were subjected to rigid military training and discipline similar to that experienced by cadets at the U. S. Military Academy. The mental and physical hazing that was instituted in the Air Corps was designed to test a cadet's respect for authority, commitment to duty and honor, and to prepare them for the rigors that they would experience later in their military careers.

Most cadets believed that the White flying instructors were conscientious. They had volunteered for the assignment at Tuskegee, thereby insuring a degree of sincerity and fairness towards the students. When friction did develop, it was usually a result of orders from higher up, or from non-flying White staff and ground personnel of lower rank, who were reluctant to accept the Black cadets and officers.

An issue that was the subject of discussions at the base from the beginning to the very end of the training program at Tuskegee was the question of the use of quotas to limit the number of Black pilots. Officially, there were denials that such quotas were imposed, but many of the pilots that trained at Tuskegee Army Air Base are convinced that quotas were in fact imposed.

In the fall of 1944, another milestone in military aviation was reached when four Black Army Service Pilots were graduated from the Tuskegee Army Air Field Basic Instructor's School to serve as the first Black Army commissioned instructors to teach cadets at Tuskegee. They were First Lieutenant Archie F. Williams, and Flight Officers Adolph Moret, Jr., Charles W. Stephens, and James O. Plinton. About the same time, Black combat veterans began returning to the States and shortly thereafter were assigned positions as instructor pilots at Tuskegee and Walterboro Army Air Fields.

The evolution of the Tuskegee training program was driven from two opposing factors. First, there was the favorable performance of the Black pilots compared to the Whites, both in school and through combat, and second, in light of these accomplishments, the officials at the top of the command level in the Air Corps and the War Department were stripped of their rationale for opposing the inclusion of Blacks in military aviation. Even so, there remained an undercurrent of prejudice and biased attitudes that persisted among the White officers at the command level.

A total of 926 pilots (including 5 Haitians) graduated from Tuskegee Army Flying School. Class 46-C was the last class to finish training at the school and graduated on June 29, 1946.

EAST COAST CHAPTER 120 Waterfront Street, Ste 420-2189 National Harbor, MD 20745 | * indicates required

|